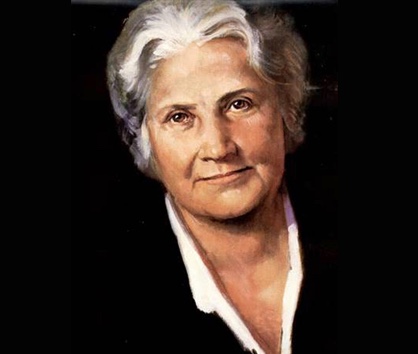

Maria Montessori was born on August 31, 1870 in the town of Chiaravalle, Italy. The Montessori family moved to Rome in 1875, and the following year the young Maria enrolled in the local state school. In 1886 she started at a technical school to become an engineer. This was unusual at the time as most girls who pursued secondary education studied the classics.

Upon her graduation, Montessori wanted to become a doctor, and despite the opposition of her father, and initially being refused entry, Montessori enrolled at the University of Rome to study physics, maths and natural sciences, receiving her diploma two years later. She then became the first woman to enter medical school in Italy, and in 1896 she became her country’s first female doctor.

She was immediately employed at a hospital attached to the university, and shortly after was appointed as a surgical assistant at another hospital in Rome. In 1897 she volunteered to join a research programme at the psychiatric clinic of the University of Rome. As part of her work at the clinic she would visit Rome’s asylums for the insane. She relates how, on one such visit, the caretaker of a children’s asylum told her with disgust how the children grabbed crumbs off the floor after their meal. Montessori realized that in such a bare, unfurnished room the children were desperate for sensorial stimulation and activities for their hands, and that this deprivation was contributing to their condition.

She began to read all she could on the subject of mentally retarded children, and in particular she studied the ground-breaking work of two early 19th century Frenchmen, Jean-Marc Itard, who had made his name working with the ‘wild boy of Aveyron’, and Edouard Séguin, Itard’s student. She was so keen to understand their work properly that she translated it herself from French into Italian. Itard had developed a technique of education through the senses, which Séguin later tried to adapt to mainstream education. Highly critical of the regimented schooling of the time, Séguin emphasised respect and understanding for each individual child. He created practical apparatus and equipment to help develop the child’s sensory perceptions and motor skills, which Montessori was later to use in new ways.

During the 1897-98 University terms she sought to expand her knowledge of education by attending courses in pedagogy. In 1898 Montessori’s work with the asylum children began to receive more prominence. The 28-year-old Montessori was asked to address the National Medical Congress, where she advocated the controversial theory that the lack of adequate provision for retarded and disturbed children was a cause of their delinquency. Expanding on this, she addressed the National Pedagogical Congress the following year, presenting a vision of social progress and political economy rooted in educational reforms. This notion of social progress through education was an idea that was to develop and mature in Montessori’s thinking throughout her life.

Montessori’s involvement with the National League for the Education of Retarded Children led to her appointment as co-director, with Guisseppe Montesano, of a new institution called the Orthophrenic School. The school took children with a broad spectrum of disorders and proved to be a turning point in Montessori’s life, marking a shift in her professional identity from physician to educator. Until now her ideas about the development of children were only theories, but the small school, set up along the lines of a teaching hospital, allowed her to put these ideas into practice. Montessori spent two years working at the Orthophrenic School, experimenting with and refining the materials devised by Itard and Séguin and bringing a scientific, analytical attitude to the work. She taught and observed the children by day and writing up her notes by night.

The relationship with Guisseppe Montesano had developed into love, and in 1898 Maria gave birth to a child, a boy named Mario. In 1901 Montessori left the Orthophrenic School and immersed herself in her own studies of educational philosophy and anthropology. In 1904 she took up a post as a lecturer at the Pedagogic School of the University of Rome, which she held until 1908.

During this period, developers of an apartment complex in Rome approached Dr. Montessori to find a way to occupy a group of impoverished children who were causing serious damage to the building while their parents were away working during the day. Montessori grasped the opportunity, bringing some of the educational materials she had developed at the Orthophrenic School. She established her first Casa dei Bambini or Children’s House, which opened on the January 6, 1907.

A small opening ceremony was organised, but few had any expectations for the project. Montessori felt differently: “I had a strange feeling which made me announce emphatically that here was the opening of an undertaking of which the whole world would one day speak.” She put many different activities and other materials into the children’s environment but kept only those that engaged them. What Montessori came to realise was that children had the power to educate themselves when they were placed in an environment with activities designed to support their natural development. She was later to refer to this as ‘auto-education.’ In 1914 she wrote, “I did not invent a method of education, I simply gave some little children a chance to live”.

By the autumn of 1908 there were five Case dei Bambini operating, four in Rome and one in Milan. Children in a Casa dei Bambini made extraordinary progress, and soon five-year-olds were writing and reading. News of Montessori’s new approach spread rapidly. Within a year the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland began transforming its kindergartens into Case dei Bambini, and the spread of the new educational approach began.

In the summer of 1909 Dr. Montessori gave the first training course in her approach to around 100 students. Her notes from this period became her first book, published that same year in Italy, which appeared in translation in the United States in 1912 as The Montessori Method. It reached second place on the U.S. nonfiction bestseller list and soon afterwards was translated into 20 different languages. It has become a major influence in the field of education and propelled Dr. Montessori towards worldwide fame.

A period of great expansion in the Montessori approach now followed. Montessori societies, training programmes and schools sprang to life all over the world. Much of the expansion, however, was ill-founded and distorted by the events of the First World War. In 1917 she based herself in Barcelona, Spain, where a Seminari-Laboratori de Pedagogiá had been created for her.

Maria nursed an ambition to create a permanent centre for research and development into her approach to early-years education, but any possibility of this happening in her time in Spain was thwarted by the rise of fascism in Europe. By 1933 all Montessori schools in Germany had been closed and an effigy of her was burned above a bonfire of her books in Berlin.

In the same year, Mussolini closed down all Montessori schools in Italy after Dr. Montessori refused to cooperate with his plans to incorporate her schools into the fascist youth movement. The outbreak of civil war in Spain forced the family to abandon their home in Barcelona, and they sailed to England in the summer of 1936. From England the refugees travelled to the Netherlands to stay in the family home of Ada Pierson, the daughter of a Dutch banker.

In 1939 Maria embarked on a journey to India to give a 3-month training course in Madras followed by a lecture tour; she was not to return for nearly 7 years. With the outbreak of war, and as an Italian citizen, Maria was put under house arrest. She spent the summer in the rural hill station of Kodaikanal, and this experience guided her thinking towards the nature of the relationships among all living things, a theme she was to develop until the end of her life and which became known as “cosmic education,” an approach for children aged 6 to 12.

Montessori was well looked after in India, where she met Gandhi, Nehru and Tagore. In 1946 she returned to the Netherlands and to her grandchildren who had spent the war years in the care of Ada Pierson. In 1947 Montessori, now 76, addressed UNESCO on the theme Education and Peace. In 1949 she received the first of three nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize. Her last public engagement was in London in 1951, when she attended the 9th International Montessori Congress.

Maria Montessori died on May 6, 1952, at the holiday home of the Pierson family in the Netherlands.